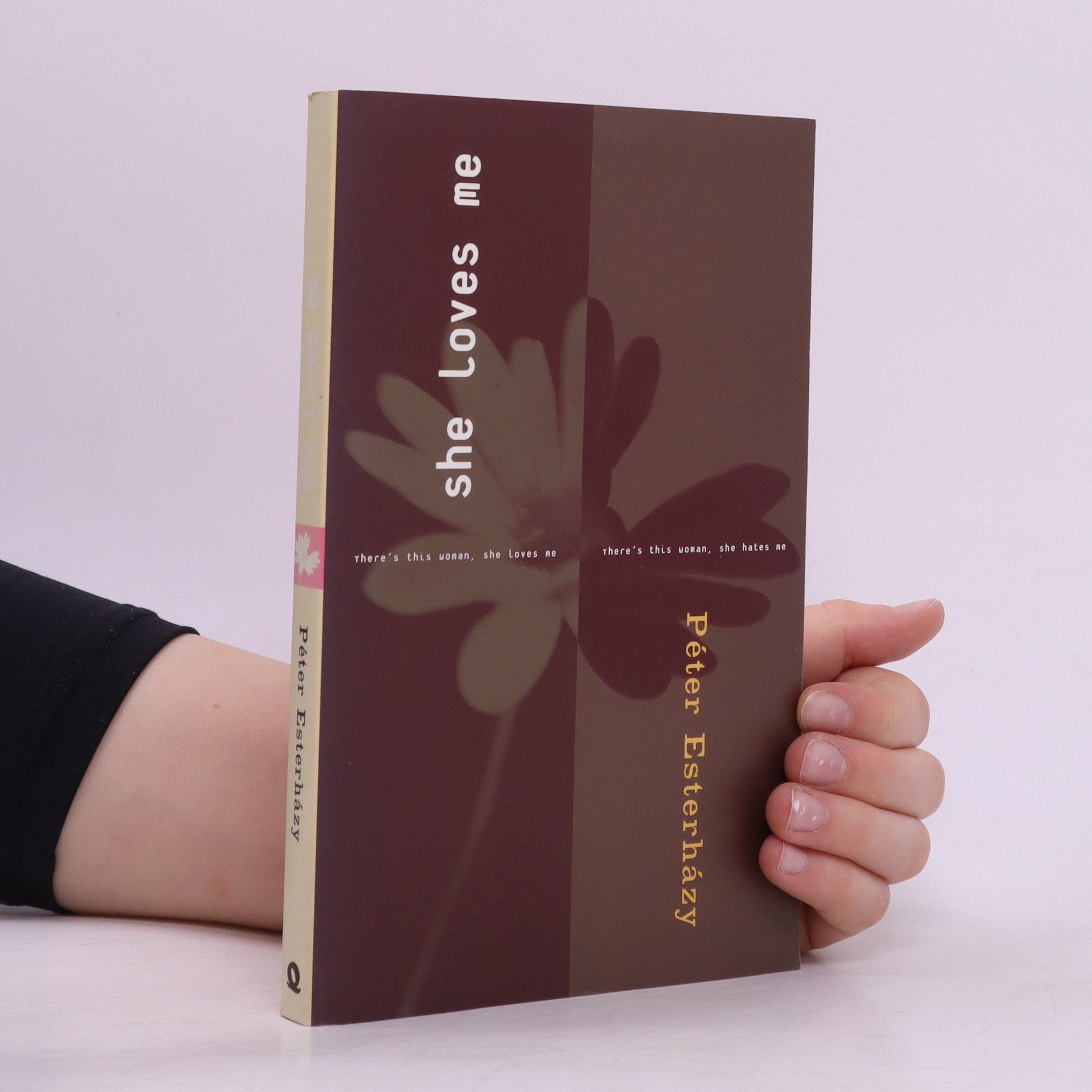

In ninety-seven short chapters Péter Esterházy contemplates love and hate, sex and desire, from the point of a view of a narrator who considers himself a great lover, a man who may (or may not) be in love with all the women in the world.

Péter Esterházy Boeken

Péter Esterházy was een Hongaarse schrijver, die wordt beschouwd als een leidende figuur in de 20e-eeuwse Hongaarse literatuur. Zijn werken worden gezien als belangrijke bijdragen aan de naoorlogse literatuur, waarbij hij diepgaande existentiële vragen en de complexiteit van het menselijk bestaan verkent met een onderscheidende stijl en intellectuele diepgang.

Celestial Harmonies

- 880bladzijden

- 31 uur lezen

The Esterházys, one of Europe's most prominent aristocratic families, are closely linked to the rise and fall of the Hapsburg Empire. Princes, counts, commanders, diplomats, bishops, and patrons of the arts, revered, respected, and occasionally feared by their contemporaries, their story is as complex as the history of Hungary itself. Celestial Harmonies is the intricate chronicle of this remarkable family, a saga spanning seven centuries of epic conquest, tragedy, triumph, and near annihilation. Told by Péter Esterházy, a scion of this populous clan, Celestial Harmonies is dazzling in scope and profound in implication. It is fiction at its most awe-inspiring. This P.S. edition features an extra 16 pages of insights into the book, including author interviews, recommended reading, and more.

A kötet fontos tanúságtétele Esterházy mindennapok finom rezdüléseire figyelő emberségének, kétségkívül európai szellemiségének. A benne foglalt írások maradandóságát pedig mi sem bizonyítja inkább, mint hogy az utolsó munka, A Kékszakállú herceg csodálatos élete múlhatatlanul az Esterházy-univerzum egyik központi darabja – a szerzői felolvasások közönségének legnagyobb gyönyörűségére. „Ez a kötet tulajdonképpen A kitömött hattyú (1988) folytatása, az azóta írtakat gyűjtöttem össze, mindent, ami nem regény és nem elefántcsonttorony-cikk. Az utóbbi kéthárom évben szívesen voltam afféle alkalom szülte tolvaj (olykor önmagamé; ezeket úgy hagytam, nem retusáltam). Ennek lehetőségét az új szabadság adta, mozgató erejét pedig a remény és a félelem, a remény, hogy itt most végre lesz valami, és a félelem, az aggódás, hogy nehogy nagyon félre menjen ez az egész. Remény, félelem – jut is, marad is. De most nem gondolom, hogy itt elvadulhat a helyzet, és nem gondolom, hogy élni tudnánk, ahogy mondani szokás, a történelmi eséllyel. Ahogy senkinek a világon, nekünk, magyaroknak sincs elképzelésünk, látomásunk a jövőről. Nem leszünk a szabadság laboratóriuma. Inkább a szabadság cselédjei…” Esterházy Péter

Javított kiadás

- 282bladzijden

- 10 uur lezen

Soha könyvet nem övezett még akkora titoktartás, mint Esterházy Péter naplóját, amely 2000. január 30. és 2002 áprilisa között készült. Eddigi életművének csúcspontja a Harmonia Caelestis című regénye volt, amelyben édesapjának, Esterházy Mátyásnak állít emléket. Az új könyvből kiderül, hogy a regény kéziratának befejezése után Esterházy megtudta, hogy édesapja III/III-as ügynök volt, és ezt követően kezdte el írni a naplót. A könyv különleges napló, amelyben Esterházy közreadja az ügynöki jelentések részleteit és ezekhez fűzött jegyzeteit. A „melléklet a Harmonia Caelestishez” irodalmi mű, amely az apa és fiú viszonyát, a kommunista rendszer természetét, történelmünket, árulást, emberi magányt és szenvedést, istenkeresést, valamint a múlttal való szembenézést tárgyalja. A mű egy ember személyes és írói sorsának megrendítő fordulatáról számol be. Esterházy álmaiban apjának magyarázza, hogy meg kell írnia ezt a históriát, amelyről senki nem tehet, és amelyben apja a szenvedő alany. Az álom után csak a fázás marad, de a jónak csak az emléke él.

Manesse Bibliothek der Weltliteratur: Lerche

- 304bladzijden

- 11 uur lezen

Das Drama eines ungelebten Lebens entfaltet sich in der fiktiven Provinzstadt Sárszeg, fernab der glanzvollen Donaumonarchie. Hier erleben die Eheleute Vajkay, nach langer Zeit wieder allein, einen unerwarteten Wandel. Ihre Tochter, liebevoll 'Lerche' genannt, verbringt die Sommerfrische bei Verwandten, was das gewohnte Dreigespann auf den Kopf stellt. Ohne die geliebte Tochter empfinden die betagten Eltern ihr Zuhause als öde und leer. Widerwillig entscheiden sie sich, ein Restaurant zu besuchen, und entdecken überraschend Freude an Essen und Gesellschaft. Dieses Experiment wird wiederholt, und allmählich tauchen sie wieder in das Leben der Kleinstadt ein, von dem sie sich lange abgeschottet hatten. Währenddessen verbringt Lerche, das unansehnliche Mauerblümchen, ihre Ferien mit dem Schreiben pflichtbewusster Briefe an ihre Eltern, ohne Freude am Leben zu finden. Mit feiner Ironie und präzisen Details schildert Kosztolányi den unerwarteten Aufbruch der Daheimgebliebenen. Für einen kurzen Moment erkennen die Eltern, wie sehr ihnen ihre Tochter zur Last geworden ist, und dennoch sehnen sie sich nach ihrer Rückkehr. Das Drama familiärer Abhängigkeiten wird schonungslos und zugleich mit Leichtigkeit dargestellt.

Als die Einführung 1986 erschien, bedeutete dies einen Wendepunkt in der ungarischen Literatur: Esterházy vollendete eine durch die Diktatur zerstörte Entwicklung der Moderne - schon das erste Wort des 900seitigen Buchs war eine Hommage an James Joyce -, und gegen die offizielle Ideologie brachte er eine neue Literatur in Stellung. Anfang 1978 sah ich plötzlich ein , Gebäude vor mir, ein , Texthaus, an dem ich bis 1985 arbeitete. Zuerst fing ich an, die einzelnen Räume zu schreiben, also die Zimmer, Säle, breiten Treppenhäuser, und so erschienen die Vor-Bände Indirekt, Wer haftet für die Sicherheit der Lady?, Fuhrleute, Kleine Pornographie Ungarns, Die Hilfsverben des Herzens. Als ich damit fertig war, begann ich das große Gebäude zusammenzustellen, baute Treppen, Querkorridore, Fenster, kleine Gesimse. Manchmal zeigte es sich, dass das Wort zu wenig war, dann verwendete ich Bilder oder , graphische Einheiten. Immer wieder hatte ich den Gedanken, das Ganze sei ein Hypertext, ein mehrdimensionaler Raum." (P. E.) Das Buch ist eine Art Enzyklopädie aus 21 selbstständigen Prosateilen, die Esterházy durch Zitate, Marginalien, Fotos, Zeichnungen und Symbolen derart untereinander und mit der Weltliteratur vernetzt, dass es sich zu einem offenen, unbegrenzten literarischen Raum weitet.

Die Frage „Was ist Literatur?“ würde er hier und heute ungern beantworten. So begann Péter Esterházy seine Vorlesungen als Tübinger Poetikdozent des Jahres 2006. Würde man diese „brave Frage“ aber folgendermaßen umschreiben: „Was zum Teufel ist Literatur?“, dann wäre es ihm nicht so fremd, über diesen „Teufel“ zu sprechen. In der für ihn charakteristischen unvergleichlichen Mischung von Witz und Ernst, von spielerischer Ironie und kritischer Schärfe, stellte der große ungarische Schriftsteller drei Abende lang dem faszinierten Publikum seine Poetik des modernen Erzählens vor. Die Geschichte des europäischen Romans und der Wirklichkeitsbezug der Literatur werden darin genauso behandelt wie sein persönliches Verhältnis zur deutschen Sprache und sein zitierender Umgang mit Lieblingsautoren wie Danilo Kiš und Deszö Kosztolányi. Über allem aber steht die Frage, wie die Sprache des 21. Jahrhunderts beschaffen sein muss, des Jahrhunderts, „in dem die Überlebenden des Holocaust sterben werden“ und uns, die Nachgeborenen, in einem „furchteinflößenden neuen Alleinsein“ zurücklassen.

Jednoduchý príbeh čiarka sto strán - Šermovacia verzia

- 248bladzijden

- 9 uur lezen

Najnovší Esterházyho román, ktorý vyšiel v Maďarsku len v júni tohto roku, možno jednoducho označiť ako autorov náhľad na možnosti historického románu, ktorého dej je zasadený do 17. storočia, teda do čias tureckej nadvlády v Uhorsku. No nelineárny čas, dekonštrukcia zaužívaných románových postupov, prelínanie sa mien a postáv z histórie aj súčasnosti, alúzia na diela rôznych žánrov svetových dejín umenia a vedy rozličných historických období robí z tejto knihy nanajvýš vzrušujúce dobrodružstvo uvažovania o najpálčivejších otázkach bytia, ba vesmíru, okoreneného o autorov svojský ironický nadhľad.