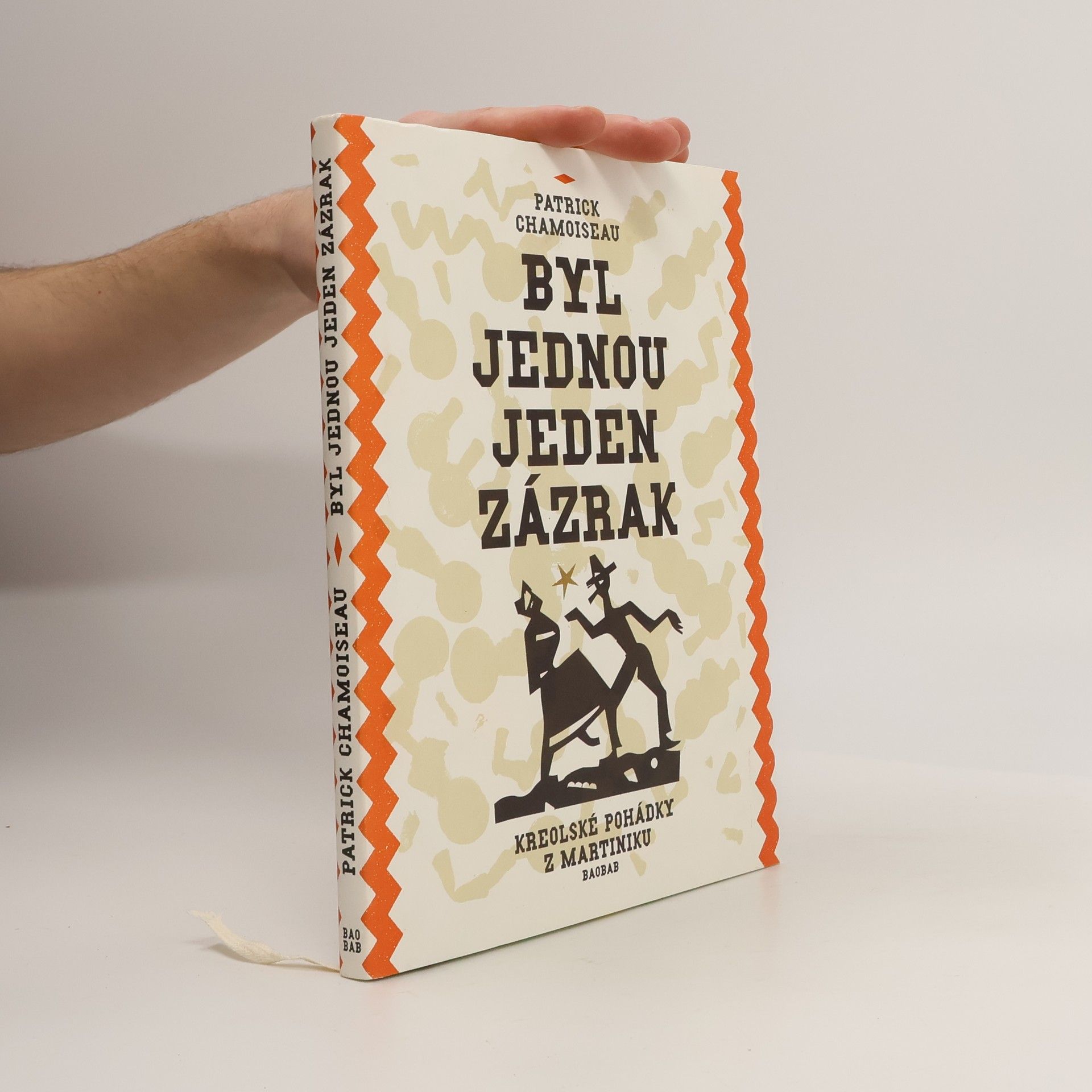

Derde Spreker Serie: Kroniek van zeven armoedzaaiers

- 189bladzijden

- 7 uur lezen

De zeven armoedzaaiers die deze kroniek verhalen, zijn 'jobbers' - manusjes-van-alles - op Martinique. Zij bezien het leven op het eiland vanaf hun plek op de groentemarkt, waar dagelijks een bonte mengeling van negers, mestiezern, Syriërs, nachtduivels en zombies samenstroomt, waar geknokt wordt om het bestaan, waar de koopvrouwen de scepter zwaaien en de mannen zich voornamelijk wijden aan de rum. Held van de kroniek is Pipi, meester van de kruiwagen. Zijn illegale boottochten tijdens de oorlog, zijn worsteling met het slavenverleden, zijn triomfen als wondertuinder en zijn noodlottige ontmoeting met een nachtvrouw: de jobbers hebben het allemaal van nabij beleefd. Op meeslepende wijze doen zij er verslag van: humor, wreedheid, poëzie, medeleven en melancholie wisselen elkaar af in dit relaas over een veranderende wereld, waarin voor jobbers steeds minder plaats is.